elcome to Jessica Chastain Network, your oldest and most complete resource dedicated to Jessica Chastain. You may better remember her as Molly Bloom in Molly's Game or Maya in Zero Dark Thiry. Academy Award winner for The Eyes of Tammy Faye, Jessica spans her career from big to small screen, seeing her not only in movies like The Help, The Debt, Miss Sloane, Woman Walks Ahead, The Zookeeper's Wife, The Good Nurse, she also played some iconic roles for series like Scenes from a Marriage and George & Tammy. Recently she registered a podcast series, The Space Within, and had a role in Memory and Mothers' Instinct. This site aims to keep you up-to-date with anything Mrs. Chastain with news, photos and videos. We are proudly PAPARAZZI FREE!

elcome to Jessica Chastain Network, your oldest and most complete resource dedicated to Jessica Chastain. You may better remember her as Molly Bloom in Molly's Game or Maya in Zero Dark Thiry. Academy Award winner for The Eyes of Tammy Faye, Jessica spans her career from big to small screen, seeing her not only in movies like The Help, The Debt, Miss Sloane, Woman Walks Ahead, The Zookeeper's Wife, The Good Nurse, she also played some iconic roles for series like Scenes from a Marriage and George & Tammy. Recently she registered a podcast series, The Space Within, and had a role in Memory and Mothers' Instinct. This site aims to keep you up-to-date with anything Mrs. Chastain with news, photos and videos. We are proudly PAPARAZZI FREE!

elcome to Jessica Chastain Network, your oldest and most complete resource dedicated to Jessica Chastain. You may better remember her as Molly Bloom in Molly's Game or Maya in Zero Dark Thiry. Academy Award winner for The Eyes of Tammy Faye, Jessica spans her career from big to small screen, seeing her not only in movies like The Help, The Debt, Miss Sloane, Woman Walks Ahead, The Zookeeper's Wife, The Good Nurse, she also played some iconic roles for series like Scenes from a Marriage and George & Tammy. Recently she registered a podcast series, The Space Within, and had a role in Memory and Mothers' Instinct. This site aims to keep you up-to-date with anything Mrs. Chastain with news, photos and videos. We are proudly PAPARAZZI FREE!

elcome to Jessica Chastain Network, your oldest and most complete resource dedicated to Jessica Chastain. You may better remember her as Molly Bloom in Molly's Game or Maya in Zero Dark Thiry. Academy Award winner for The Eyes of Tammy Faye, Jessica spans her career from big to small screen, seeing her not only in movies like The Help, The Debt, Miss Sloane, Woman Walks Ahead, The Zookeeper's Wife, The Good Nurse, she also played some iconic roles for series like Scenes from a Marriage and George & Tammy. Recently she registered a podcast series, The Space Within, and had a role in Memory and Mothers' Instinct. This site aims to keep you up-to-date with anything Mrs. Chastain with news, photos and videos. We are proudly PAPARAZZI FREE!

How Jessica Chastain Won the Hollywood Game by Refusing to Play

Tim Teeman

November 14, 2017

Articles taken from Town & Country.

The star is every woman, but her role in Hollywood has been anything but conventional.

or 45 very unique minutes, Jessica Chastain kidnaps this reporter. We do not meet in a swank Tribeca hotel, as planned, but instead in a butch black SUV that speeds around Manhattan. She is rushing to catch the Hampton Jitney, the bus that ferries smart New Yorkers to their weekend idylls, and first there are things to be picked up en route, which an assistant jumps out of the car periodically to do.

One of my favorite parts of being an actress is being a detective.

“This is quite the caper,” Chastain says, casual in white shirt and blue jeans, her hair tied back. One might have assumed that a famous Hollywood actress—she received Oscar nominations for her roles in The Help and Zero Dark Thirty and is in the midst of launching a major campaign for a new Ralph Lauren fragrance—would prefer a more private mode of transport to the Hamptons.

But even though she had just married Italian count and fashion exec Gian Luca Passi de Preposulo at his family’s fairy-tale estate in Treviso this past summer, Jessica Chastain has something of the common touch—a fact that was evident to anyone who saw her don a pink knit hat to walk in the Women’s March in Washington in January.

Plus, the cloak-and-dagger feel to our chaotic afternoon echoes, if unintentionally, her latest big project, the film Molly’s Game. Aaron Sorkin’s movie-directing debut tells the story of former champion skier Molly Bloom, who came to run high-class, high-stakes poker games in Hollywood and New York at which the players included Tobey Maguire, Ben Affleck, and Leonardo DiCaprio, as well as art world scion Helly Nahmad (who would later be jailed for his part in the illegal ring).

When Chastain first met Bloom, the actress and her real-life counterpart went to an art show. Chastain wanted to see how Bloom presented herself. “One of my favorite parts of being an actress is being a detective,” Chastain says. She wanted to know which style icons Bloom, known for never failing to turn it out, looked up to. The stunning cocktail dresses and suits that Bloom wore in real life, from Dolce & Gabbana and Roland Mouret, are among the film’s many delights.

“How she looked was the ultimate equalizer,” Chastain says. “In a room full of powerful men, her meticulous appearance leveled the playing field. Her dress was her armor, and she dressed carefully—sexy but not vulgar. I had a lot of fun working with costume designer Susan Lyall and pulling inspiration from pop culture icons.”

I’m working hard to break free of stereotypes that the film industry has created and nurtured around women.

The clothes are used to convey power, not as aids of seduction. There is no romantic storyline in the movie, no sex scenes. “She’s an accomplished, successful woman, and she doesn’t trade romance for leverage,” Chastain says. “I am not one to go for traditional female roles, because I don’t think traditionally female characters are very interesting, and I don’t think they represent real life. I’m working hard to break free of stereotypes that the film industry has created and nurtured around women.”

“Some people have noted that we never see any scenes where Molly has a boyfriend,” Sorkin says. “It’s interesting, because, as far as I know, no one mentioned that about Brad Pitt in Moneyball.”

He adds that Chastain’s preparation and commitment were something to behold. “On most movies, three to five pages is a full day. Jessica and Idris [Elba, who plays Bloom’s lawyer] had to shoot 45 pages their first week, all dialogue. If they hadn’t shown up ferociously prepared, we wouldn’t have a movie. She’s as hardworking as they come. She’s who you want to be in a trench with.”

Before shooting, Chastain met with poker players who had played with Bloom, and she attended games “where people lost a lot of money, which was a bit shocking to me. I felt I was going to vomit and faint at the same time.”

She deflects questions about DiCaprio, Affleck, and Maguire (none of whose names are used in the film). “For me this movie is not about gossip. It’s the story of this woman who makes a lot of mistakes and gets knocked down a lot but keeps standing back up.” And it satisfied her requirements for a role. “It’s about whether the character is flesh and blood, a real human being with her own desires separate from a husband or boy or love interest,” Chastain says. “I think the industry is beginning to examine itself and how it has perceived female roles. I’m seeing a lot of really interesting discussions, and I do think it’s changing.”

But for Chastain, the personal is political, and Hollywood is just the tip of the iceberg. “We have a long way to go in the world in all industries,” she says. “If I’m in the situation where I have equal experience to the other actor and my role is just as significant, there is no reason why I should be paid less. It’s not really part of my world anymore, because I just won’t accept it.”

Some people have noted that we never see any scenes where Molly has a boyfriend. It’s interesting, because no one mentioned that about Brad Pitt in Moneyball. —Aaron Sorkin

Via social media Chastain is a committed activist, tweeting against the repeal of Obamacare and in support of the #TakeAKnee protests. She quickly commented on Harvey Weinstein’s behavior, praising condemnations from others and tweeting, “I was warned from the beginning. The stories were everywhere. To deny that is to create an environment for it to happen again.”

But like many Americans she often finds the Twitterverse dejecting (“Sometimes it just makes me feel like I don’t want to get out of bed”), so she looks to her work as a vehicle for change. “With The Martian, I was excited that young girls were seeing that movie and knowing it was possible to be a female commander on a space mission. I believe that the energy you put out into the world is what you get back, so I’m trying to put something positive out there, something to inspire girls to go into science, to run for office, to try to join the space program.”

Tate Taylor, her director on The Help, recalls the way Chastain navigated a clash between her ideals and her professionalism on set. “She’s a tireless animal lover and a vegan, and her character, Celia, had to carry a chicken upside down to a tree stump for slaughter,” he says.

Chastain was upset (even though no real slaughter would take place), “but she said, ‘Celia would kill her own chicken, wouldn’t she? Give me a moment with the chicken.’ She went off behind a tree, holding the chicken, kissing it, telling it how much she loved and respected it and that she was really sorry she was going to have to carry it upside down. Then she said she was ready, and she picked it up by its feet and did the scene.”

Chastain found joy in the Women’s March: “How much love and support there was—all ethnicities, sexual orientations, gender identities—just this melting pot of acceptance. I am happy to stand alongside and march for any minority to have equal rights. But I’m not into anything that incites violence, that magnifies hate, because it becomes contagious. I like what Martin Luther King Jr. said: ‘Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that.’ That’s how I try to approach my political resistance and my life: with hope and love.”

Chastain grew up “all over” Northern California. Her mother Jerri raised her as a single parent. “It was tough for her,” Chastain says. “My mom had me when she was 17 years old. It’s insane when I think about it—my mom had five kids.” The youngest, a brother, lives with Chastain in New York.

There is no reason why I should be paid less than a man. It’s not really part of my world anymore, because I just won’t accept it.

The actress describes herself growing up as “withdrawn and ill at ease.” She hated her red hair and kept it chopped short. “I always marched to my own drum but was then lonely because I didn’t fit in,” she says. “I didn’t look like everyone else—I was a nine-year-old girl with short hair. I was teased. Maybe because I felt invisible I wanted someone to pay attention to me.”

As a young girl she started a theater company, funded by sales from a lemonade and cookie stand. Her grandmother took her to a production of Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat; she remembers the show starting with a girl like her onstage. “She was playing make-believe for a living,” Chastain recalls thinking. “That was her job. It just seemed like the most wonderful thing.”

Chastain’s first role, in 1998, was as Juliet in a production of Romeo and Juliet by a San Francisco–area theater company. After attending Juilliard, she mixed TV—roles in series as varied as Veronica Mars and Law & Order: Trial by Jury—with theater, including parts in The Cherry Orchard and in Othello at the Public Theater opposite Philip Seymour Hoffman.

In 2011 she made a huge leap to the A-list with the release of three films in quick succession: The Help, Jeff Nichols’s Take Shelter, and Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life. “I kind of loved that,” she says of the blizzard of movies. “It made me so excited. No one really knew anything about me, because I’m very private and don’t want to be an actor who plays my personality over and over again. I like the idea that you discover me through little tiny hints in each of the roles I play. Every role I’ve ever played has a little bit of me in it, even the evil ones.”

But offscreen Chastain says she has a “very boring, happy, easy life. I’m very happy to not be gambling, or risking my life, or driving at 125 miles per hour. I don’t need to jump out of an airplane. I can keep my chaos onscreen.” Taylor agrees with this self-assessment. “Jessica is willing to do almost anything for a character,” he says. But in real life “she’s someone who takes the subway. It’s a cliche?d thing to say that she’s just a normal, good-hearted person who happens to be famous, but she is, and that’s my favorite kind of actor.”

Taylor has some upcoming projects in the works with Chastain. Also on tap for her are roles in Xavier Dolan’s first English language movie, The Death and Life of John F. Donovan; the next X-Men film, Dark Phoenix; and the superhero action flick Painkiller Jane, which she will star in and produce.

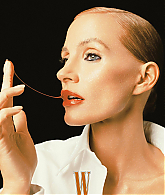

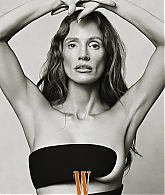

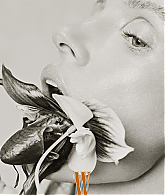

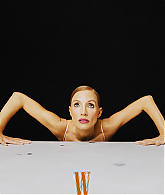

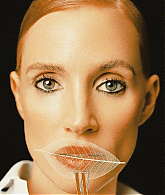

Chastain also recently became the face of the new Ralph Lauren fragrance, Woman, which has a campaign that’s right up her alley. “I’m interested in celebrating women in all of their complexities—truly authentic, self-realized women,” she says. “Ralph and I both believe in the importance of empowering women, and this campaign embraces the blurred lines of gender and crushing stereotypes.”

That doesn’t mean she doesn’t take pleasure in certain traditional acts. “Getting married was a significant thing,” she says. “I’m very happy with my husband, and it was wonderful to be with all my friends and family and his friends and family and celebrate love.”

Just when I ask if she would like to have children, Chastain says our time speeding around Manhattan is up, and she bids me a cheery farewell. Our driver wedges the SUV right in front of the Jitney. Jessica Chastain has made her bus.